Prisoner-of-war camp

Prisoner-of-war camp in St Ouen's Bay

|

|

This article by T E Naish, who commanded the Royal Engineers in Jersey from 13 September 1914 to 20 December 1919, was first published in the 1955 Annual Bulletin of La Société Jersiaise

|

The War Office in August 1914 sent instructions that a 'temporary' Prisoners of War Camp was to be prepared at once in Jersey. There was only one place which contained both the necessary buildings and the necessary open space for such a camp to be quickly prepared, and accordingly the Royal Jersey Horticultural and Agricultural Grounds at Springfield were taken over.

The cattle sheds were furnished with continuous sloping wooden platforms to act as beds, they were boarded in, sanitary buildings were erected, water and gas laid on from the town mains, the enclosure was secured by barbed wire along the existing walls and by a new barbed wire fence 10 feet high, and 8 sentry platforms were erected.

This work was completed under the writer in September 1914, but was never used for prisoners of war. It was occupied by troops of the New Army (4th South Staffordshire Regiment), and later on by the Army Service Corps as a Supply Depot.

At the same time, Brighton Road School was taken from the States of Jersey and the necessary alterations made for its use as a Prisoners of War Camp for officers. This was never used as such, and was occupied later as a Military Hospital (after the necessary modifications had been made), and made an admirable Hospital down to the time that it was handed back to the States of Jersey in 1919.

Larger camp requested

In December 1914 the War Office enquired if a site could be found for a prisoners of war camp of 1,000 men in Jersey. Owing to the intensive cultivation of the soil in Jersey, there are very few large open sites available, and on all such sites the principal difficulty was the obtaining of a sufficiently large water supply for a large body. All houses in Jersey beyond the limits of the St Helier water mains are supplied by wells, the yield of which is very limited. All streams in this Island are fouled by the proximity of houses, and unfit for drinking.

The War Department owns two large sites in Jersey, one at Les Landes for rifle practice, and the other at the Quennevais (or Blanches Banques) for manoeuvres.

The former site is in rock (a few inches in most places below the surface) and the wells there sink very low in the summer and have to be supplemented during the musketry season by rain caught from the roofs of the buildings.

Accordingly the writer examined the latter site for its water possibilities. The surface here is of a sand rising in places to hills 170 or 180 feet above the sea, but on the flat portion having a height of something like 30 feet above the rock. The under¬lying rock in the north west portion is Archsean Shale, and in the South East portion is granite.

The period being the wettest time of the year it was very difficult to estimate whether the amount of water would be sufficient during the dry season. For example, on the site chosen for a well the water level rose that year to 6 feet of the surface, causing the greatest difficulty in sinking the well (the sand becoming like quicksand under the pressure of water), whereas in the next dry season it had sunk to nearly 30 feet from the surface and was only I or 2 feet above the rock level below the sand.

Further details of the water supply will be given later.

Practically no details were available of what a prisoners of war camp should be like; but the writer decided to base it on the requirements of a permanent camp for a battalion of infantry, of which some type plans were available.

Wooden huts

The living huts were planned to be of wood, made in sections in England, as the War Office had made large contracts for the supply of such huts. About 40 such huts were ordered in the first instance. It was decided to line these huts with sheets of j-ply wood, which proved most suitable and practically damage proof.

The size of the huts was 60 feet by 15 feet internally with a floor space of 900 square feet, and were calculated to contain 30 men. The actual huts received were supplied by a firm of Norwich.

They were heated by enclosed coal stoves (Canadian pattern) and were lighted by electric light.

While the huts were being made in England, the foundations were pushed on with locally, each hut being supported on 39 pillars 9in square of brick or concrete.

The roofs were originally of tarred felt, but the quality supplied by the contractor was poor and did not stand the weather, so that a year later all the huts were covered with corrugated iron nailed on top of the felt.

All the remainder of the accessory buildings were designed to be of corrugated iron (walls and roof) on wood framing. The cookhouse and wash-ups were unlined, the bath house was lined with asbestos cement sheets, and so was the drying house. The ablution rooms and latrines were unlined. The hospital was lined with wood match boarding varnished.

Outside the enclosure, the cookhouse, drying house and bath house were unlined, the office block was lined with asbestos cement sheets, the company office and store was lined with varnished wood, and also the clerks' quarters (for the senior NCOs of the clerical staff and guard), the staff quarters (living quarters for officers of the staff and guard) was lined with asbestos sheets, and the cells of the guard block were lined with large sheets of tinned iron.

Some of the later built huts outside the enclosure were lined with match boarding laid longitudinally and inside the enclosure with sheets of Swedish compo-board, in both cases because three-ply wood had by then become unobtainable.

1,500 prisoners

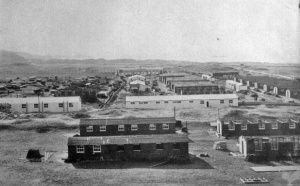

The general layout of the camp is shown in the illustration, this represents its appearance from 1917 onwards when it had been considerably enlarged and held over 1,500 prisoners, besides 150 guard, and a staff of 20 or 30 officers not being included in the above.

The area enclosed was approximately a square of 300 yards, the guard buildings being entirely outside this area.

The exact position of every building (with provision for reasonable extensions) had to be settled before anything could be done towards laying out the water supply and drainage systems.

It was most necessary to get on with the construction of these at once, as it could not be hurried if good work was expected.

The design of the drainage system especially presented difficulties. For temporary camps occupied a few weeks during the year, a dry-earth system is satisfactory, but this implies a contract for carrying away and burying the refuse. Two or three weeks refuse can be disposed of during a year, but few farmers or others have land where they could dispose of a year's continuous refuse without constituting an intolerable nuisance.

Water borne drainage was therefore decided on, and it was considered that the septic tank constructed for the St Peter's Barracks drainage near Le Braye Slipway, St Ouen's Bay would be large enough to take the sewage from the Blanches Banques Camp also.

A drainage system must have no dips or rises but must be of a steady gradient throughout to be self cleansing; levels were therefore run upwards from the septic tank and it was found that by using the highest parts of the ground available there was just sufficient gradient. The drain pipes at Blanches Banques were all laid on concrete, and were carried across dips on the ground on planking supported on small piles.

The lines of drainage and the buildings requiring drainage (latrines, ablution rooms, bath house, cookhouse, wash-ups, drying house, hospital, guard block, clerks quarters and staff quarters) were therefore sited first and the other buildings grouped round them.

Water and drainage

The water supply was designed to supply the same buildings, every building that required water also required drainage.

A cast-iron pipe was designed to carry the water from the reservoir to the camp and this three inch pipe was carried right through to the hospital. On this three inch pipe were established hydrants at intervals, the reservoir being sited on a "col" or " saddle" about 80 feet above the camp gave good pressure of water for fire purposes.

Smaller pipes of galvanized wrought iron branching from the three inch main supplied all the buildings enumerated above.

All these lines of pipes were most carefully laid out so that there might be no dips or rises anywhere, since dips would permit sand to collect, and rises would permit air to collect and block the flow.

It was decided to form the reservoir of galvanized wrought iron tanks of 1,000 gallons each, connected together. This was for speed and simplicity of erection; it also enabled any portion of the tanks to be cleaned independently without cutting off the water supply. Six rows each of 5 tanks connected end to end gave a total capacity of 30,000 gallons.

After considering various methods of lighting such as acetylene and petrol gas, it was decided to light the camp by electricity.

The principal objection to this was that as it would be practically the first electric lighting installation in Jersey, it would be difficult to get spare parts and stores locally, it would also require a class of skilled labour to run it that was not available locally.

One of the principal reasons for deciding on electricity was that the laying of pipes for acetylene gas or petrol gas would cut up the sandy ground considerably just as hundreds of tons of materials for the buildings were being carted over it, and the pipes would probably be crushed by the traffic passing over them unless very deeply buried, whereas the electric light wires could be taken overhead.

Electricity generator

A Pelapone oil engine was selected to generate the electricity; this type of engine is similar in appearance to a motor car engine but runs on paraffin after starting on petrol. The dynamo stands on the same bed plate and both engine and dynamo run at 800 revolutions per minute - no belt is therefore required (a great saving in engine room space).

The system was duplicated - the smaller engine of three cylinders and 13½ horse power could run a normal lighting load, and the larger engine of four cylinders and 17½ horse power could run the electric centrifugal pump at the well half a mile off at the same time.

Duplication was essential in order to carry out periodical repairs and overhaul.

The lamps employed were metallic filament of 25, 15 and 10 candle power, the 15 candle power lamp being most generally employed; there were in the end about 350 lamps throughout the camp, not including those that were fixed on the barbed wire boundary fence as a stand-by.

By using electricity a large saving was also made in annual upkeep, as it was found possible to save a second engine room (and the necessary personnel) for pumping from the well by using an electric pump operated entirely from the electric light engine room.

This electric pump ran at 2200 revolutions per minute being direct driven and on the same bed plate as an electric motor supplied by current from the electric lighting installation. Though the pump delivered 6,000 gallons per hour (and more under favourable circumstances) it was only 6 inches in diameter, and the small space occupied by electric motor and pump enabled a further large saving to be made in the size and cost of the pump house.

Boundary lights

As it was essential that the lighting of the boundary fence should not fail, even for a minute, it was decided that each light should be self contained, or independent.

Lamps lit by paraffin gas (vaporized as in the well known Primus stove) with an incandescent mantle were chosen and installed when the camp opened - they were hoisted to the top of long poles after being lit.

These were very satisfactory as long as too strong a wind was not blowing, but a violent wind so cooled the vaporizing apparatus that it would not function properly; and after various improvements were tried without complete success, these type of lamps were finally abandoned for acetylene lamps.

Finally 24 of these lamps were installed (6 on each side) and later one more at each of three corners - a total of 27.

In these lamps the acetylene gas was made in an apparatus on the ground and conveyed to the lamp by a flexible tube, the lamp being lowered for lighting and cleaning. The glass globes gave continual trouble by becoming cracked in wet and stormy weather, and finally a lantern was designed and made locally which acted perfectly. As this lantern was made out of an old carbide tin fitted with narrow panes of glass cut from broken sheets, it cost practically nothing.

A Hospital was designed and erected inside the compound with 44 beds. The ground plan was an H. There were four general wards each of 10 beds, at the outer end of each ward was a bath room and other sanitary arrangements, at the inner end an attendant's room with small window looking into the ward.

There were also four special wards of beds. In the centre was the medical officer's room, the kitchen, store rooms, etc, and the whole was connected by covered corridors. The whole was of corrugated iron on wooden framing supported on brick pillars as foundations, and lined with varnished match boarding. A small isolation hospital was also provided.

Soon after the camp was opened the question of a YMCA hut for the recreation of the guard was raised, and the hut that had been erected by local subscription for the 11th South Staffordshire Regiment at Don Bridge was moved down and erected at the camp.

American YMCA

Later the American YMCA (before the entry of the USA into the war) took up the question of providing recreation for the prisoners of war. It was finally arranged that the American YMCA should buy all the materials, and that the prisoners should provide all labour for erection. A very fine hut was the result, as there were many excellent mechanics in the camp; it was generally in the shape of a cross and the separate reading rooms and games rooms could be thrown into the main hall by folding back partitions when extra accommodation was required for theatrical purposes.

To prevent the escape of the prisoners a barbed wire fence was erected round the whole camp 10 feet high. This was carried on wooden uprights 9 inches by 4 inches, with a bracket at the top so that the top wires overhung the base on the inner side. The lower wires were close together, the upper further apart, there were vertical wires at intervals for stiffening purposes. A sloping apron was added on the inside, also a horizental network of barbed wire on the ground line to make crawling beneath the fence difficult.

Later on, loose tangled coils of barbed wire were added underneath the apron.

There were eight sentry platforms provided, one at each corner, and one in the centre of each side. The floor level of each platform was above the top of the barbed wire fence.

Each platform had 2 sentry boxes, opening inwards - thus one of the sentry boxes always gave shelter whichever way the wind blew.

Later on each platform was connected with the Guard Block by a telephone, and electric push bells were installed at intervals along the boundary fence for sounding an alarm in the Guard Block. The designs for the various buildings were taken in hand successively by the writer, and calls for tenders were sent out successively.

From five to six contractors were asked to tender for each contract, this involving the preparation of five to six plans and five to six specifications for each contract.

Contractors

Most of the contracts were let locally, Mr C J Le Quesne being successful in obtaining most of them, several contracts went to Mr J T Ferguson, Mr N H Harris was responsible for the drainage and water supply, and Mr T R Blampied for the boundary fence and platforms.

Of outside firms, Messrs Browne & Lilly of Reading was successful in obtaining the contract for a large number of the buildings and carried out their work very satisfactorily, being the only firm that was not behind their contract time. Messrs Boulton & Paul of Norwich built the hospital. Messrs Hampton & Sons of London carried out the whole of the electric light work, and also contracted for some of the huts when the camp was extended.

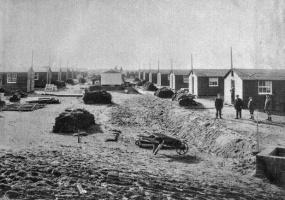

Mr E Farley of First Tower carried most of extensions to the guard buildings outside the enclosure. The illustration shows the camp as completed March 1915. Taken from low sand-hills to the East of Guard buildings, looking West to St Ouen's Bay and showing the Corbiere lighthouse and La Rocco tower.

The camp was opened on 20 March 1915, the first party of prisoners arriving on that date and the second on 22 March.

The total strength of the two parties was 1,000 and the strength of the guard was 100, clerical staff and officers not included.

The number of prisoners was increased by 500 on 7 July 1915, making a total of 1,500 and the strength of the guard was also increased to 130.

The prisoners originally had the advantage of ten huts near the cookhouse being assigned as dining huts, holding each 100 men at meals; but when the strength was increased these huts were taken for living huts and three more huts were built.

More huts were also built for the guard; and the staff quarters (which included the officers' mess) was enlarged.

No work offered

In England the prisoners of war were very largely employed on agriculture and on other civilian work in the national interest; but though efforts were made to have the men similarly employed here there was no local response.

Accordingly, in 1917 it was decided to remove all except 300 prisoners to England, and these left in two parties on 13 February and 16 February, 1917.

The remaining 300 were employed during the potato season in loading the steamers with potatoes bought by the British Government.

After the completion of the potato season, this party also left, and the camp was closed on 29 August 1917.

The camp was reopened in April 1918. By the Hague Convention, which was strictly observed by the British Prisoners of War Department, non-commissioned officers cannot be compelled to work - accordingly the prisoners of war sent were all NCOs. The last party of these prisoners arrived on 12 April 1918, making a total of 1,000.

The camp was finally closed in October 1919, the first party leaving on 5 October and the second on 6 October.

Commandants

There were in all six Commandants during the whole period: Lt-Col G. Haines, Lt-Col Gordon Cumming, Major A C Richards, Major W A Stocker, Major Allpress and Captain O Pulley - all these were given the temporary rank of Lt-Colonel while commanding the camp.

The prisoners were on the whole very well behaved, they were, in fact, much better disciplined on arrival than after they had been in the camp some time; the result of over indulgent methods. The writer has seen over 100 men scattered in twos or threes throughout the camp come to attention as he walked through it, some men being so far off as almost to be out of sight; later on a British Officer had to pass very close to a prisoner of war before he took any notice.

The writer employed a number of prisoners on Royal Engineer works at St Peter's Barracks and elsewhere. The southern entrance was enlarged practically entirely by prisoners of war labour, and the present parade ground was entirely made by them. The widening of the main roads through the Barracks, and the construction of branch roads was also carried out by them; they also did most of the levelling of the recreation ground in the SB angle of the barracks. As large a number as 60 daily were employed for some time.

A great deal of work was also done by the prisoners of war at the camp itself, on water supply, painting, road making etc.

Interpreter

The man who acted longest as interpreter and under foreman was a German who had lived in America, called Karl Paul. This man's share in the Great War was both remarkable and speedy. He happened to be in Hamburg at the outbreak, and was promptly impressed much against his will.

He was immediately given a naval uniform and sent out on the mine-laying Konigen Luise, which was as promptly sunk by the British Navy off Harwich, and Karl Paul spent the rest of the War in captivity and did not regret it as far as could be noticed.

His English had a mixture of both German and American accents, and he generally referred to a fellow prisoner as "that bloke" (pronounced blo-ak).

One man who acted as an interpreter of a casual party of prisoners told the RE foreman in charge that he had been a Professor at Oxford University before the war, and stated that he knew a well-known member of the Société Jersiaise, and further had stayed in Jersey on holidays in St Peter's parish. He did not return again to work, as wheel barrow work was evidently not his strong point.

There were several escapes from the camp, mostly of single individuals who slipped out in ways not always discovered, but all were readily recaptured. Only on one occasion were the wires found to be cut after an escape.

One man was found to be missing at roll call, was searched for in vain; but found again inside the camp after 2 or 3 days. One man escaped, found his way into St Helier, and stopped a Sergeant near Fort Regent to ask him the way to Government House as he had something of importance to communicate to the Lieut-Governor. The Sergeant induced him to come with him to the guard-room where he was confined. He was mad.

Escape attempts

There were 2 organised attempts to escape.

In the first place the prisoners selected one of the A line of huts (that is the line nearest the road), from which to commence their tunnel. They had been allowed to put up a summer-house adjoining this hut; from this summer-house they burrowed under the floor of the hut, and then dug a shaft diagonally downwards until they reached a depth at which the sand was fairly solid. A prisoner stationed in the summer¬house, himself unseen, watched the sentry outside the barbed wire, and gave the necessary warnings.

The size of the horizontal tunnel was just large enough to take a man stretched out, but not large enough for him to raise his knees, the miner at the head of the shaft had to wriggle to his post of work, and wriggle back.

The sand proved just hard enough to stand without lining, being at that depth slightly moist.

The excavation was done by a tin can, and the proceeds placed on a flat tray which was drawn back and forth by means of a long string.

The tray when drawn back was emptied by the party under the floor of the hut, the miner then drew it forward again between his legs. The sand accumulated under the hut was got rid of at night when the wind was blowing, which scattered it in all directions and left no trace.

Below the floor the prisoners used a lamp made of a small biscuit tin, and burning beef fat, this is now in the possession of the writer.

The tunnel was carried right under the road, and then inclined upwards; the prisoners then pushed up small holes to the surface about one inch in diameter for ventilation, this was done by means of the jointed rods used in the camp for clearing the drains.

Discovery

One day, an NCO of the staff was walking on the short grass on the further side of the road, and using a walking stick, when the stick partly disappeared down a hole in the ground. This curious event led to investigation, and the whole was discovered.

The next attempt was also made in A lines, in this case a square of the floor was very neatly sawn through and replaced and thus access was obtained to the underside of the floor.

In this case a small party of the prisoners, six or seven, actually escaped, travelled north during the night to St Ouen's parish, and then returned on their tracks. They carried tinned food with them and blankets, and were noticed by several people but not stopped.

They were finally tracked and surrounded in a small wood near St Brelade's Bay. It was alleged that the guard fired a volley at them, before calling on them to surrender. Both of these tunnels were carried out by subscription, the men doing the dangerous and unpleasant work being paid for it. They were many months in being executed.

Peculiar game

With regard to the recreation of the prisoners, the ground set aside for sport was equal to a third of the whole area of the camp, say 300 yards by 100 yards. They played association football at first, but not later on; they also played a very peculiar game of rounders. But their principal game was a sort of lawn tennis or badminton played with a football.

A string was stretched between two posts some 50 feet apart about 6 or 7 feet above the ground. Four or five men or more played on each side, and the game was to punch the ball over the" net" without letting it bound on the ground more than once. Any number of men on the same side might punch the ball so long as it did not touch the ground on that side more than once.

Some prisoners constructed a gravel lawn tennis court, which later was concreted, but it was not used much. They had also gymnastic apparatus in the open air.

Of course they had a band, and a very good one; the prisoners were also excellent at choral singing. They held many concerts and theatrical entertainments in their YMCA hut.

Among the first prisoners were many naval men captured in the first naval engagements of the War; they wore caps with Konigen Luise (the mine layer), Mainz (the cruiser) and of various torpedo boat divisions. Nearly all were Germans, not Austrians, or Turks. The later NCO prisoners were mostly soldiers.

With regard to the water supply, it has been mentioned that the very wet season prevented the well being dug as deep as had been intended. Further, a trench, in which a drain pipe was laid, had to be dug in the greatest difficulties (owing to the superabundance of water turning the sand into quick sand) in order to carry off the surplus water from the well and prevent its rising above the floor of the well house and flooding the electric motor.

In digging this drain trench interesting Neolithic remains were found, some of which are preserved in the museum of the Société Jersiaise.

The upper layer of sand was white and loosely compacted; it was of very irregular depth. Below that was a yellow sand closely compacted; one could carve a pattern on this sand and it would stay for days.

Between these two layers at one particular point was a black layer tapering out at the ends, but nearly three inches thick in the centre of the section made by the drain trench. This black layer was full of limpet shells and small pieces of pottery; there were also fresh-water mussel shells, bones of deer etc. and a polished stone axe. A shattered vessel was found full of limpet shells apparently placed ready to cook.

Neolithic remains

The trench excavation was slightly widened by the members of the Société Jersiaise during their search, but there must still be in the ground a large store of Neolithic remains to be found by further widening the trench.

Though miles of trench were dug for water and drainage as well as for foundations, this was the only place in which the black layer was found.

The shortage of water became pronounced at the end of the summer of 1915, the springs being lowest in the Blanches Banques area in November. Search was accordingly made for other sources of supply, and many wild suggestions were made by amateur engineers in the camp or elsewhere, such as pumping water from the sea for sanitary purposes, or from St Ouen's pond.

Finally, the writer came across the small spring on the La Moye Golf course, now known as Watercress Spring. Though the trickle from this spring only ran 30 yards before disappearing in the ground, the writer at once saw its possibilities as it was situated at an even higher level than the 30,000 gallon reservoir and could supply the latter by gravity (thus saving pumping, and collecting every drop of the 24 hours' run of the spring).

Accordingly this spring was opened up and paved, a collecting tank sunk in the ground, and a 3in galvanised iron pipe (diminishing to 2½ in where the fall became greater) was laid from the collecting tank to the reservoir. This galvanised iron pipe was laid without dips or rises and so was self cleansing; it followed the contours of the sand hills accordingly in order to get cover.

Later on the well itself was lowered in the dry season; and another spring opened up near the well and its supply led into the well to reinforce it.

This latter spring, called the Neolithic Spring, did not come out on the surface. A well was therefore dug to the water level and below, and a drain trench dug up to meet the bottom of the well. Thus when the valve at the bottom of the well was opened, all the water in the well could be drained off without pumping and the spring running in gave a constant supply.

Concrete reservoir

Later still in 1918, a reinforced concrete reservoir of cell pattern was constructed to collect the whole 24 hours flow of this spring, and once a day this reservoir was opened up into the well pump which threw the water collected up into the reservoir, taking only 2 hours pumping to do it.

Readings of the depth of the well were taken daily, and of the flow of the springs weekly. It was found that either heavy rains or drought showed their effects 3 months after. The low water period was November, the highest water was March or April. There was always a superabundance of water in March, for instance in March 1919 there was over 300,000 gallons per day from the two springs. But a dry summer (June, July, August) meant that the springs would yield comparatively very little three months later (September, October, and November) and this was the time they were low in any case.

There were many boards of visitors sent from time to time by the War Office to visit the Camp. In addition there was the inspection made on 20 April 1916 on behalf of neutral nations by the Embassy of the United States.

The result of the visit was given in a white paper, presented to Parliament and published by authority. The report mentioned 883 military and 314 naval prisoners at that time.

Model camp

The following quotations may be made :

- " The infirmary (hospital) has its own kitchen and sanitary arrangements and offices, and seems to be a model of what such a hospital should be."

- " This camp seemed almost to be a model of its kind, and the men appeared to be in extraordinary good physical condition".

- Prisoner of war's funeral Added 2022

Prisoner of war's card

These pictures, mostly taken by photographer Albert Smith, show what life was like at the camp. Click on any image to see a larger version